Sri Lanka’s human-elephant conflict is costing lives and the Sri Lankan government plans to adopt ‘elephant corridors’ to avert the crisis. But experts say approach is unscientific.

By Malaka Rodrigo

Wildlife experts question the wisdom of adopting “elephant corridors” in Sri Lanka to end the country’s deadly human-elephant conflict, calling instead for a more science-based approach.

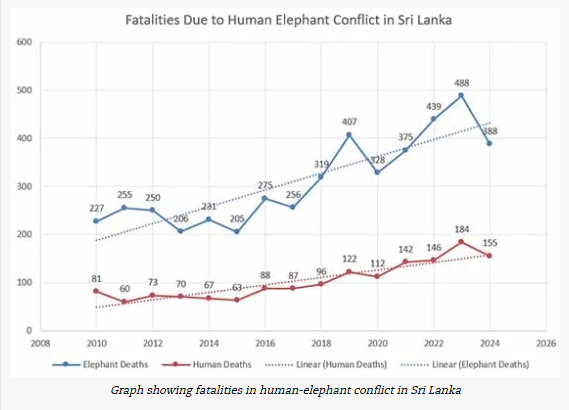

Nearly 5,000 elephants and 1,600 people have been killed in the last 15 years in clashes between elephants and humans in Sri Lanka, home to one of the largest remaining populations of Asian elephants, according to official figures seen by SciDev.Net.

Gunshots, electrocution and homemade explosives hidden in food, called hakka patas or jaw bombs, are the leading causes of elephant deaths.

Human deaths occur mostly when elephants raid crops and homes in search of food and water. But they are sometimes also caused by irresponsible behaviour such as approaching wild elephants, especially under the influence of alcohol, and harassing or chasing them.

To try to end the conflict, the Sri Lankan government plans to introduce elephant corridors, based on long-distance migration models used in other countries.

According to Sri Lanka’s deputy minister of environment, Anton Jayakody, four major elephant corridors have been selected as first step. Sources close to the ministry say these will be designated as protected areas to mark World Environment Day on 5 June.

However, Prithiviraj Fernando, chief scientist and top official at Sri Lanka’s Centre for Conservation and Research, thinks the strategy ignores the basic behaviour of the country’s elephants.

‘Wishful thinking’

“Sri Lanka’s elephants are non-migratory, so corridors don’t work when elephants don’t move between parks,” Fernando tells SciDev.Net.

Fernando, who used GPS tracking to study elephant movements for decades, says that 70 per cent of Sri Lanka’s less than 6,000 remaining elephants live outside protected areas, and many stay outside these areas even when roaming for food.

“The idea of confining elephants to parks is based on wishful thinking, not science,” he says.

Last year, Sri Lanka’s Department of Wildlife Conservation recorded 157 human deaths and over 200 injuries linked to elephant encounters. Property and crop damage claims exceeded 3,700 cases, costing the government Rs385 million (US$1.3 million) in compensation.

“Most of the victims are poor farmers in rural Sri Lanka,” says E.G. Wickramasinghe, divisional secretary of the town of Galgamuwa in the North Western Province — one of the hardest-hit areas.

Government compensation stands at one million Sri Lankan rupees (around US$3,330) per human fatality. But for many families, this does little to replace the loss of a breadwinner, says Wickremasinghe.

Failed attempts

In the first four months of this year, 150 elephants and 50 humans had already died, leading authorities to resume traditional tactics such as elephant drives. In one such effort, rangers attempted to drive the elephants into Wilpattu National Park in northwestern Sri Lanka. But the operation resulted in elephants congregating in a village, intensifying conflict in that area.

A controversial elephant holding ground, established in 2013 to detain rogue elephants, ended in failure, with most animals unaccounted for after relocation.

“There is no record of a successful elephant drive in Sri Lanka as elephants return and they’re more aggressive because they associate humans with trauma,” says Sumith Pilapitiya, elephant biologist and former head of the Department of Wildlife Conservation.

In Sri Lanka, electric fences designed to deter elephants often fail due to poor maintenance, misplacement and limited community involvement. Elephants are also intelligent enough to learn techniques to breach the fences, making them less effective.

Despite mounting evidence, successive governments have ignored scientific advice looking for instant results, according to Fernando.

“The science is clear. Protected areas are at carrying capacity, [meaning the area can’t support any more of the species] so the elephant conflict mitigation must adapt,” he says.

Science-based plan

One attempt to shift towards evidence-based solutions was Sri Lanka’s National Action Plan for the Mitigation of human-elephant conflict, developed by a presidential committee chaired by Fernando in 2020. The plan proposes community-managed electric fences, mobile fencing around seasonal farmland, and managed elephant ranges to allow elephants to roam freely in specific landscapes.

These interventions proved successful when piloted last year and both elephant and human fatalities declined. However, since a change in government in late 2024, the action plan has been set aside.

Conservationists warn that abandoning science-based policy could reverse recent gains.

“The National Action Plan is a scientifically grounded, peer-reviewed framework and Sri Lanka’s best chance to reduce conflict gradually and sustainably,” Pilapitiya tells SciDev.Net.

“The human-elephant conflict doesn’t have instant solutions, so it is of utmost importance to carry out science-based solutions to get results.”

Emerging from its worst economic crisis, Sri Lanka has cut conservation budgets, impacting wildlife efforts. But the real obstacle to implementing evidence-based solutions is weak political will and poor understanding, says Pilapitiya.

Hemantha Withanage, executive director and senior environmental scientist at the Centre for Environmental Justice, says that unplanned development — particularly agricultural encroachment — is a major driver of the conflict.

Withanage also stresses the need to use science and technology to improve yields from existing farmlands, to lessen the need for new areas to be cleared. He urges authorities to declare any remaining forest patches that are important elephant habitats as protected areas.

“Unless land use is regulated and wilderness preserved, the problem will only escalate,” he adds.

This story has been sourced from SciDev.Net.

Photo courtesy of Hippopx.