Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals will be a challenge as the COVID-19 pandemic has been singled out as the primary reason for a rise in global poverty.

By Thalif Deen / Inter Press Service

The UN’s highly-ambitious goal of eradicating extreme poverty by 2030 has been severely undermined by a rash of problems worldwide, including an escalating coronavirus pandemic, continued widespread military conflicts and the devastating impact of climate change.

According to published estimates, more than 700 million people have been living in poverty around the world, surviving on less than $1.90 a day.

But the fast-spreading pandemic, whose origins go back to December 2019, has been singled out as the primary reason for a rise in global poverty – for the first time in 20 years.

A World Bank report, which was updated last October, says about 100 million additional people are now living in poverty as a direct result of the pandemic.

For almost 25 years, extreme poverty — the first of the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) — was steadily declining. Now, for the first time in a generation, the quest to end poverty has suffered a setback, says the report.

Sir Richard Jolly, Institute of Development Studies, Sussex, UK, told IPS the World Bank is emphasizing that world poverty has been rising — after many years where in countries with positive economic per capita growth, it suggested that poverty had fallen, or soon would.

Admitting he was “a fan” of the UNDP’s annual Human Development Report (HDR), he said: “So, for me, multi- dimensional poverty is a more realistic and relevant indicator”.

“I want to know what’s been happening to life expectancy, access to education and incomes of the poorer sections of society, those below a poverty measure or median income”

For instance, the numbers and percentages of the population below $10,000 in many countries, lower for some, especially in Africa. Even if by income measures poverty is rising, a multi-dimensional measure is much better, he said.

“What are those in UNDP’s HDR office saying about recent poverty trends?” asked Sir Richard, who was a former Trustee of Oxfam and chairman of the UN Association of the UK.

Deepening poverty and worsening inequality

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres says the pandemic has “laid bare” challenges –such as structural inequalities, inadequate healthcare, and the lack of universal social protection – and the heavy price societies are paying as a result.

Ending poverty sits at the heart of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and is the first of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Despite this, poverty and hunger, Guterres said, are on the rise, following decades of progress.

In his New Year message last week, he said the world welcomes 2022 “with our hopes for the future being tested”: by deepening poverty and worsening inequality, by an unequal distribution of COVID vaccines, by climate commitments that fall short of their goals and by ongoing conflicts, divisions, and misinformation.

“These are not just policy tests. These are moral and real-life tests. And they are tests humanity can pass — if we commit to making 2022 a year of recovery for everyone,” he declared.

Need major policy changes to reduce poverty by 2030

In an interview with IPS, Roberto Bissio, Coordinator of Social Watch, an international network of citizen organizations that monitor how governments meet internationally-agreed commitments, pointed out that the World Bank once again underestimates poverty by measuring it with the extremely low benchmark of $1.90 a day.

Further, by assuming that the tide lifts all boats equally it claims that the COVID-induced poverty “tsunami” of 2020 is being turned around by economic growth in 2021.

“This ignores the conclusion of the World Inequality Report 2022, showing that inequalities have been exacerbated, particularly in the South, where states don’t have deep pockets to fund emergency social protection”.

The Bank is right that SDG1 on reducing poverty won’t be achieved by 2030 without major policy changes, but neither will SDG10 on reducing inequalities, said Bissio, who was also a former member of the Civil Society Advisory Committee to the Administrator of the UN Development Programme, and has covered development issues as a journalist since 1973.

“And it shamefully ignores that World Bank promoted policies of privatization and deregulation make the inequalities worse,” he argued.

“Instead, the policies recommended by the infamous and now discontinued “Doing Business” report of the World Bank, are still part of the conditions imposed on countries to receive emergency from the Bank”.

The institution that claims to have poverty reduction as its main mandate is part of the problem, not of the solution, said Bissio, who is also international representative of the Uruguay-based Third World Institute.

The past is part of our present that shapes our future

Vicente Paolo Yu, Senior Legal Adviser at the Third World Network, told IPS the setback in 2020 to the fight against global poverty due to the Covid pandemic exacerbates the impact of other crises such as climate change, biodiversity loss, and the development gap on the global poor, particularly those in developing countries.

“Global poverty and inequality among and in all countries, climate change, biodiversity loss, and unequal pandemic responses are among the present-day results of historical injustices on the Global South committed in the name of Western civilization and globalization,” he said.

“The past is part of our present that shapes our future. These crises are linked and cannot be fought effectively through piecemeal efforts or in silos.”

Global poverty and inequality exist not because people are not hard working in their own homes and communities but because the way that the global economic, financial, and trade system is set up makes it difficult for poor peoples and countries to get out of poverty, he argued.

Developing countries that have recently managed to succeed in cutting poverty have been those that have implemented diverse development policies, said Yu, who is a former Deputy Executive Director of the South Centre in Geneva.

Hence, poverty and inequality are not natural phenomena but are borne out of the actions and decisions taken by human societies. They can also be reversed by human decisions, he noted.

“Failing to act together as a common human community on all fronts on poverty and inequality and their various manifestations in the root causes and impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss, and pandemic responses leads to the denial of human choices and opportunities, violations of human rights, and increased human insecurity, powerlessness, and exclusion for peoples, their communities, and their countries,” declared Yu.

Fighting these must be through a broad and systemic effort across the world founded on a deep sense of urgency and understanding of equity and justice as public goods in undertaking interlinked actions in the economic, social, and environmental fields. It is about choosing to create the conditions for human dignity and a decent life for all rather hoping for charity from the wealthy, he added.

“The continued existence of deep poverty and inequality for many peoples across the globe, compounded by the climate, biodiversity and pandemic crises, is injustice writ large — particularly when seen against the technological and industrial advances and capital accumulation of a relative few”.

“It is against the tenets of all faiths and human goodwill to refuse to act against the injustice of poverty. We should not simply look away and call for charity. We need to act with courage and conviction to correct injustice, redress wrongs, and achieve liberation from poverty and inequality.”

The year 2022, he predicted, should be the year when all peoples come together to set each other free from the shackles of global poverty and inequality.

This piece has been sourced from Inter Press Service

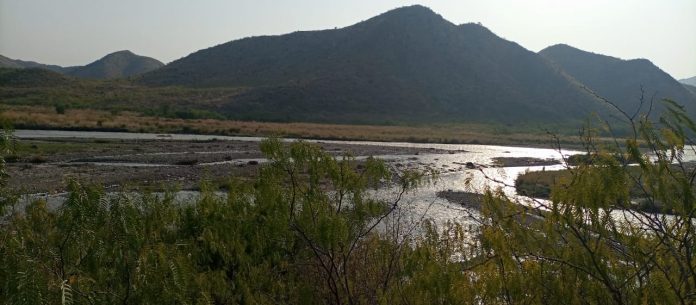

Image: In India, five out of six people in multidimensional poverty were from lower castes.

Credit: UNDP India/Dhiraj Singh